We may receive commissions from purchases made through links in this post, at no additional cost to you.

It’s essential to understand soil pH as a gardener, but it’s especially important if you’re planting fruit trees. Growing fruit in the wrong pH range can result in all kinds of problems – nutrient deficiencies, stunted growth, a lack of fruit, and even plant death.

Knowing the pH of your soil and what that indicates will help you determine what fruits will grow best in your garden with the least effort. It will inform many aspects of plant care, such as watering, fertilizing, and troubleshooting any issues that come up.

Read on to dig into (sorry for the pun) information about soil pH, why exactly it’s important for fruit trees, and how to raise or lower the pH of your soil. I’ve also included a handy chart of the pH ranges for many common fruit plants.

Table of Contents

- Soil pH 101

- The Importance of Soil pH for Fruit Trees

- How to Check Soil pH

- To Make Soil More Acidic (Lower pH):

- To Make Soil More Alkaline (Raise pH):

- Adjusting pH in Containers

- Soil pH Ranges for Common Fruits

Soil pH 101

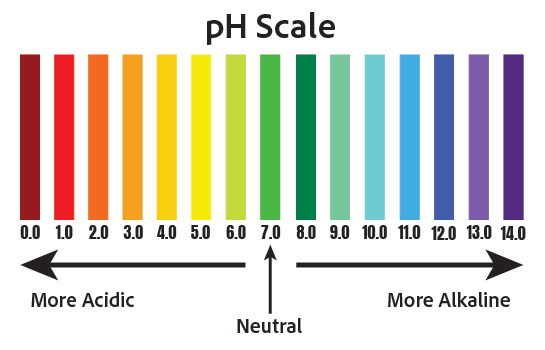

Soil pH is a measure of how acidic or basic the soil is. It is indicated on a logarithmic scale of 0.0 to 14.0, where 7.0 is neutral, less than 7.0 is acidic, and more than 7.0 is basic. The numbers on the scale are related by a factor of ten – so, a pH of 4.0 is ten times more acidic than a pH of 5.0.

Curious about any garden-related terms? Click on a highlighted word in the text, or visit The Fruit Grove Glossary to find out more.

Things that Affect Soil pH

Everything related to the soil – from rainfall to fertilizers to the rocks, minerals, and organic matter present – will affect its pH. Soil can be made up of many different rock components, all of which have different levels of acidity (granite, for example, tends to be more acidic, while limestone is alkaline).

Other things, such as the amount of organic matter or the use of certain fertilizers, help determine the pH of soil. The decomposition of organic material generally makes the soil more acidic. Also, utilizing fertilizers that contain a lot of ammonia or urea will quickly lower the pH (increase acidity).

Areas with higher rainfall also tend to have more acidic soil. The water frequently passing through the soil leaches basic nutrients, like calcium and magnesium, out and replaces them with acidic elements such as aluminum and iron. Therefore, dry, arid regions tend to have more basic soil.

The amount of sand or clay in the soil also matters. Sandy soils tend to be neutral to slightly alkaline, particularly if there is low rainfall. However, I live in the “pineywoods” of East Texas, and the prevalence of pine trees and decent annual rainfall has made our very sandy soil more acidic.

Clay soils are typically alkaline (high pH). It can be difficult to change the pH of heavy clay soil, but it’s relatively easy to alter the acidity of sand. On the other hand, it’s also easier to overcorrect sandy soil and overshoot the acid level you’re aiming for.

How is pH measured?

Soil pH is usually measured by making a solution of water and soil. The amount of free hydrogen ions (the nucleus of a hydrogen molecule without its accompanying electron) in the compound determines the level of acidity.

More of these positively-charged hydrogen ions means a higher acidity, or a lower number on the pH scale. Fewer hydrogen ions (or rather, more negatively-charged hydroxide ions) indicates a more basic solution, or a higher pH. These ions react with different soil elements differently, affecting how the plant absorbs different nutrients.

Alkalinity vs. pH: What’s the Difference?

The terms alkalinity and pH are often used interchangeably, and they are closely related, but they actually measure slightly different things. The pH level shows whether a solution is acidic, basic, or neutral by measuring the acidity (the amount of hydrogen ions present).

Alkalinity indicates the buffering capacity of a solution. Buffering capacity is the ability of a compound to resist a change in pH, and has to do with the amount of dissolved limestone in the soil or water. I like to think of this as changeability – how easily the pH can be altered.

Soils with high alkalinity have a high pH (basic), because they have a higher buffering capacity. This is important when discussing how to adjust your own soil pH, because alkaline soils with a high pH level (such as clay) are harder to alter.

The Importance of Soil pH for Fruit Trees

Soil pH is one essential part of the overall health and vitality of your soil. It’s crucial to take soil pH into account when planning your fruit garden. The soil where a fruit tree is planted will directly determine how the plant grows, absorbs nutrients, bears fruit, and withstands stress.

Learn about another key factor in growing healthy fruit trees here: Soil Drainage for Fruit Trees: Everything You Need to Know

pH directly affects what nutrients are available for your fruit trees. Every plant needs to be situated in soil within a particular pH range in order for it to absorb the nutrients it needs. If a fruit tree is deficient in some nutrient, there’s a good chance the deficiency can be corrected by fixing the soil pH.

A lack of essential nutrients affects everything about how a fruit tree grows: its vigor, ability to fight disease, cold tolerance, how it withstands water stress, and its ability to form, develop, and ripen fruit.

Outside of the optimum pH range, some nutrients become over-available to the point of toxicity. In very acidic soil (pH below about 5.5), manganese, iron, and aluminum become more available and potentially more toxic. Calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and molybdenum can’t be absorbed by most plants in highly acidic soil.

In very alkaline soil with a pH over about 7.5, high (potentially toxic) amounts of calcium, sodium, and magnesium are available. Many nutrients such as iron, manganese, phosphorus, and boron become less available to the plant’s roots.

Or, in a more generalized way: Extremely acid soils lack macronutrients and extremely basic soils lack micronutrients.

The pH also affects the type of microbial activity in the soil. Many beneficial bacteria prefer neutral to slightly alkaline soil, while fungi tend to like neutral to slightly acidic soil. Growing fruit outside of the recommended pH ranges means all of the good microbes can’t benefit the plant.

How to Check Soil pH

There are several simple ways to check your soil pH. I recommend starting with a comprehensive soil test, such as those that can be found inexpensively through your local county extension service. This will give you an idea of your overall soil pH and composition. (Find yours here.)

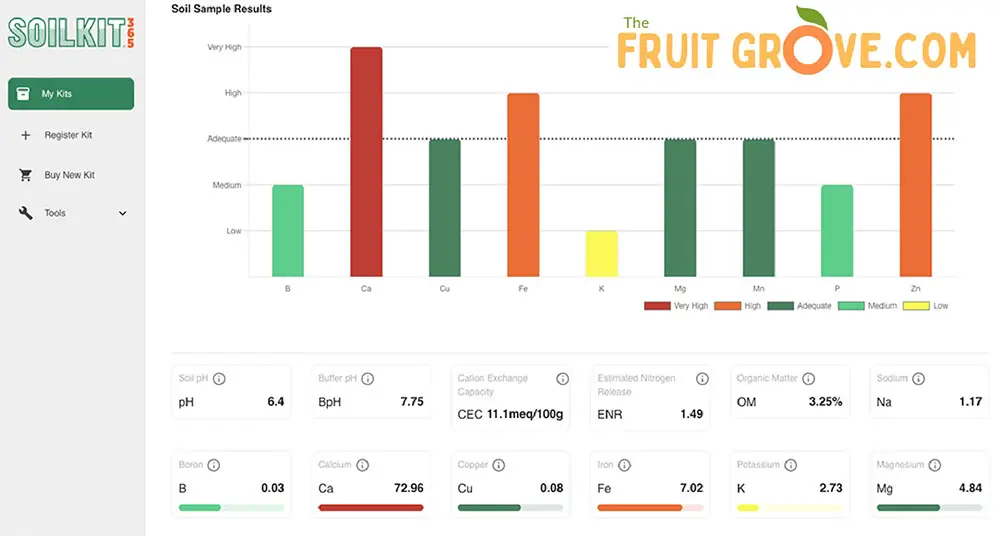

Another great option is to use a mail-away service such as SoilKit. I used SoilKit to test the soil in my own garden, and I have been very happy with the process and the results.

The procedure is simple – collect soil samples from four spots in your garden, mail them in the pre-paid envelope, and SoilKit will provide a breakdown of your soil nutrient composition, pH, and other information. They also give specific recommendations about how to amend your soil according to the results (see a sample of my results below).

Finally, I always keep an inexpensive soil testing kit like this one on hand so I can check individual spots in my garden, or to test the pH of soil in containers. I also frequently use this soil pH and moisture meter, especially for my potted fruit trees.

To Make Soil More Acidic (Lower pH):

If your soil pH is too high for the fruit trees you want to grow, there are a few things you can do to try to lower it. In general, it’s harder to lower pH than it is to raise it, and it takes more time and upkeep.

Signs that your soil isn’t acidic enough include iron chlorosis, or leaves that turn yellow with green veining. Yellowing leaves in general are an indicator of nutrient deficiencies, but there’s a good chance the problem is actually with the pH of the soil.

The following are the most common amendments for acidifying soil. Some products will adjust pH faster than others, so consider the timing in deciding what to use. In general, the more gradual the pH change, the longer it will last.

Aluminum Sulfate or Elemental Sulfur

Aluminum sulfate (also called “alum”) is made up of aluminum, sulfur, and oxygen. It’s very fast-acting because it reacts quickly with the soil, and can lower pH within a matter of days or weeks (source). On the other hand, it’s more expensive than elemental sulfur, and you need to use a lot more. It’s also easy to over-apply, leading to a toxic buildup of aluminum in the soil, which can also reduce available phosphorus.

Elemental sulfur is generally more recommended for lowering soil pH. It’s inexpensive and easy to apply. However, it needs more time to be effective since soil bacteria have to slowly convert it to sulfuric acid. The speed at which this happens depends on factors like how big the sulfur granules are, the soil moisture and temperature, and the bacteria present in the soil. It could take several months to see a change in pH with elemental sulfur.

Both elemental sulfur and aluminum sulfate need to be worked into the soil to be most effective. Keep these products away from leaves and grass to avoid leaf burn. Find helpful charts with application rates (depending on how much you are trying to lower the pH) of both of these products here.

Can you use Epsom salt to change soil pH?

Epsom Salt (magnesium sulfate) is not a good choice for lowering pH, even though it contains sulfur. You would have to use huge amounts to see a difference in the acidity, which would be toxic to plants. Read more about the Epsom salt/pH myth here.

Pine Bark

The acidity of pine bark mulch is typically between 3.7 and 4.0, which makes it a great soil amendment for lowering pH. Simply spreading pine mulch around acid-loving plants, such as blueberry bushes, can lower the soil pH over time.

You can also dig in pine bark fines (sometimes marketed as orchid bark) when you prep the soil for planting. As the pine bark breaks down, it will help acidify the soil.

As I mentioned above, the long-term breakdown of pine bark and needles in my garden has contributed to fairly acidic soil overall (average pH of 6.4, according to my soil test results), which is great for most fruit trees. But when I planted blueberry bushes, I dug in some pine fines and peat moss (see below) to lower the pH even further. Since I wasn’t trying to make a huge pH change, I went the slow-and-steady route.

Learn more about how to prepare the soil for planting blueberries here:

Peat Moss

Sphagnum peat moss is also very acidic, with a pH ranging from 3.4 to 4.8. Adding peat moss to the soil can take your pH from neutral to slightly acidic (or from alkaline to neutral), but it won’t be as effective if you are trying to make a bigger shift on the pH scale.

Peat moss is more expensive than pine bark. There is also serious concern about the environmental impact of harvesting peat moss (read more about that here).

An easy way to adjust the soil pH right at a plant’s root zone is with fertilizer. Certain nutrients affect the soil pH by either raising or lowering it. Applying an acidifying fertilizer around blueberry plants, for example, can effectively lower the pH in that immediate area.

Visit this site for more information.

To Make Soil More Alkaline (Raise pH):

Raising the pH of soil tends to be a little simpler than lowering it. If you need to neutralize your acidic soil, here are the best options for soil amendments.

Garden Lime

Garden lime is simply ground or crushed agricultural-grade limestone. Adding lime to your soil is a great way to neutralize acidity because it’s high in calcium, an alkaline element. It’s also inexpensive, cost-effective, and easy to use.

You can purchase agricultural lime in four different forms:

- Pulverized lime is very finely ground, so it is quickly effective.

- Granular or pelletized lime has larger particles, which makes it easier to handle and less likely to clog a garden sprayer. It takes longer for it to be effective at raising pH, however, because of the particle size.

- Hydrated lime (calcium hydroxide) neutralizes soil much more rapidly than other forms. It’s very effective, but use with caution since it’s very easy to over-apply.

- Dolomitic lime contains magnesium in addition to calcium. It’s a good choice if the soil has a magnesium deficiency in addition to a low pH.

The smaller the limestone particles, the more quickly it will effectively raise the pH. The composition of the soil will directly impact how much lime is needed to increase pH. For example, soils high in clay need more lime than those low in clay in order to make the same pH change.

The soil texture, the amount of organic matter, and what plant you intend to grow in the area all affect how much lime is needed. Always follow the package instructions for application rates. Start on the conservative side – you can always add more.

Apply lime in the fall or winter so it has time to become effective for the next year’s growing season. For best results, lime must be incorporated into the soil. Moisture must then be added so the lime can react to the soil and neutralize the acid.

Note that you may need to apply lime more frequently with very sandy soil. (Remember, the buffering capacity is lower, so the pH is quicker to change but quicker to revert back to “normal.”)

*NOTE: Raising and lowering methods (such as adding lime or sulfur) typically only last 1-3 years. Left alone, the soil will revert back to its original pH. Test the soil annually and continue amending as needed.

Wood Ash

Soil pH can also be raised by applying wood ash, but it isn’t as effective as lime. Wood ash contains a lot of potassium and calcium, plus phosphate, boron, and other micronutrients. It works well if it’s applied regularly, especially in sandy soils.

Avoid using too much wood ash – if the pH rises too much it could affect nutrient availability. It’s recommended to use no more than 10 pounds of wood ash per 100 square feet of soil. Also, avoid putting wood ash directly on tender seedlings or plant roots to avoid burning.

Adjusting pH in Containers

Your best bet for adjusting the soil pH for container fruit trees is to pick (or make) a soil mix with the right pH in the first place. Many commercially available potting soils will fall in the range of about 6.2-6.8, which is perfect for most fruit trees.

You can also find acidic soil mixes that are optimized for acid-loving plants such as blueberries. One such potting soil that I recommend is this Coast of Maine Organic Potting Soil.

As I mentioned above, using acidic fertilizers are perfect for adjusting the pH in a small area, like a container. The Fox Farm Happy Frog Acid-Loving Plants Fertilizer is perfect for in-ground or potted fruit trees and shrubs that need a lower pH.

If the pH of your potting soil is too far removed from the plant’s ideal range, the simplest solution may be to repot the plant with fresh potting mix.

Soil pH Ranges for Common Fruits

Most fruit trees, shrubs, vines, and other plants will happily grow in soil with a pH between 5.5 and 7.0. So if your soil falls in that range, you may not need to adjust the pH at all. Observe your plant and watch for any signs the pH is off (such as yellowing leaves, lack of growth, stress).

When all is said and done, the most inexpensive and eco-friendly way to deal with your soil pH is to work with it rather than against it. Grow fruits that are suited to the soil you already have, rather than what you wish you had (I speak from experience). You’ll see bigger, better harvests and gardening will be so much more satisfying – and less work!

Below is a list of the pH ranges for commonly grown fruit plants. I used several sources to compile this list, including this one and this one. Use this as a starting point to see what fruits might be compatible with your existing soil.