My dad grew up eating persimmons from the giant wild trees that grew on his family’s farm in Ohio. That’s what persimmons are to many people…a homey, sort of old-fashioned flavor from childhood. Persimmons have a rich history in America, from their seeds being used in the civil war as buttons for soldiers, to using the pulp for all kinds of comforting baked goods.

In the South, in particular, persimmons have been a big part of the food culture. So much so, that many people assume that persimmon trees can only grow in warm, southern areas. But the American persimmon’s native range reaches all the way up to Connecticut…hardly a tropical climate. Asian persimmons, although native to subtropical regions, can be surprisingly hardy too. So just how cold-tolerant are persimmons? And which varieties can survive the harsh winter weather?

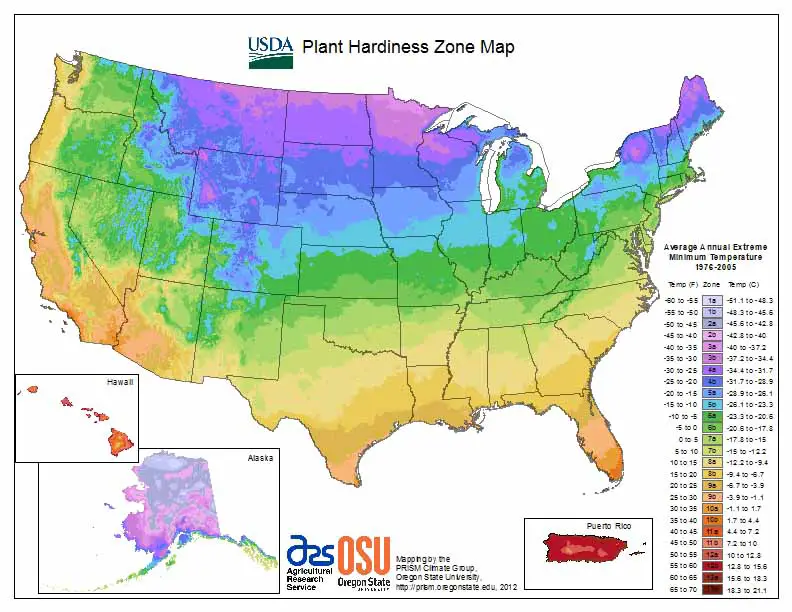

The most cold-tolerant American persimmons (‘Meader’, ‘Yates’) are hardy to USDA zone 4 (-30°F/-34.4°C). The hardiest Asian persimmons (‘Great Wall’, ‘Tan-Kam’) can survive in zone 5 (-10°F/-23°C). Winter survival is also dependent on climate, humidity, wind, elevation, tree age, and other factors.

There is a lot of mixed information out there about the cold hardiness of different persimmon varieties. The zonal range on the plant tag doesn’t give you the whole story, especially when you factor in the wild weather fluctuations and polar vortexes of recent years. In this article, we’ll dig into the cold tolerance of different persimmon trees, how to protect them in winter, and which varieties will do best in cold climates.

How cold can persimmon trees tolerate?

The general answer to this question is, American persimmons (Diospyros virginiana) grow in zones 4 to 9 (-25°F/-32°C), and Asian persimmons (Diospyros kaki) are typically hardy in zones 7 to 10 (0°F/-18°C). But there’s a lot more to it than that.

Zonal ranges are indicators of average low temperatures for that region. There are other, arguably more important, factors that will play into how well a persimmon tree will survive winter in your area.

For example, coastal regions will generally have a narrower temperature swing than inland areas of the same zone (ie, Seattle vs. Atlanta). Humidity, elevation, and wind chill will change how a plant reacts to the weather. Different microclimates in your yard, how much snow you get, and even the tree’s age and size will all affect cold tolerance.

Another example – I live in Texas zone 8b. The area around Eugene, Oregon (in the northwest U.S.) is also zone 8b but is just 60 miles from the Pacific Ocean. Both areas have similar average winter lows, but Eugene’s average high temperature is in the mid-80s. Texas regularly has weeks of summer heat in the 90s and 100s. Humidity and precipitation vary widely too.

Texas and Oregon may be able to grow the same persimmon trees according to zone, but how those trees tolerate the winter (and other weather) may be very different. One of the biggest factors in persimmon tree hardiness is the duration of cold weather.

In my area, temperatures begin warming up toward the end of February, but we are prone to late frosts in March. Persimmon trees break dormancy based on warmth, not a particular amount of cold (chill hours), so the warm early spring may make my tree bud. A late frost could kill the buds and damage the tree, setting back my persimmon crop for the whole year.

In northern climates, persimmons tend to leaf out much later, maybe not even until early summer. This is a good thing – it means the tree is less likely to be damaged by those pesky late frosts. This really has little to do with how cold-tolerant that specific tree is. Even hearty persimmon varieties are known to be severely damaged or killed by just a mild spring frost, if the tree has already begun to grow.

In short, know your climate. As a safety measure, choose a cultivar that is tolerant to half a zone north of you, just as a precaution against freak winter temperatures. If you live on the northern edge of a persimmon’s hardiness, find a spot in your yard where things tend to warm up a little sooner (a microclimate). A site near a fence or wall, where the sun reflects heat, could offer your tree a little extra protection.

For more tips on choosing a site for your persimmon tree, check out Planting a Persimmon Tree: Where, When, and How to Do It.

Do persimmon trees need frost to ripen?

Persimmon trees do not require a frost to ripen, contrary to folklore. Persimmons typically ripen between September and December, depending on variety, and some American persimmons may ripen as late as March. Persimmons can be picked when firm, then will continue to ripen off the tree.

This old wives’ tale persists, even though it has been thoroughly debunked. The reality is, many persimmons happen to be ready for picking around the time of the first frost, but that’s because they are a fall fruit. American persimmons fall off of the tree when they are fully ripe, but one tree may drop fruit from September to February.

Asian persimmons typically mature a little later in the fall, but most will ripen before frost. In fact, a frost could damage a still-growing Asian persimmon tree, depending on how severe it is (more on that below).

Ideally, a persimmon tree should be dormant by the time severe winter weather hits. Dormancy, which works a little like hibernation in mammals, protects the tree from cold. In cold climates, American persimmon trees will definitely have a better chance at survival through the harsh winter. But what about Asian persimmons?

Related: American vs. Asian Persimmon Trees: What’s the Difference?

Will Asian persimmon trees survive a freeze?

Most Asian persimmons (Diospyros kaki) are hearty to about 10°F, with some doing well down to 0°F. An established Asian persimmon tree might experience some dieback in extreme temperatures of a short duration. A longer below-normal freeze is likely to kill the tree.

Asian persimmons originated from China thousands of years ago and were later brought to Japan, Korea, and other countries. They were introduced to North America in the 1850s and have been successfully cultivated here ever since. Asian persimmons prefer warm climates with milder winters, but some cultivars can be grown as far north as USDA zone 6.

If temperatures – including windchill – are just a few degrees lower than the zonal average, an Asian persimmon may partially die back, but would probably survive. A short hard freeze that warms up again within about a day will likely cause minimal lasting damage.

But what if there are exceptional, extended low temperatures one year? Sometimes, as in the historic winter of 2020 in North America, a freakish storm could wipe out otherwise hardy trees. The reality is, this is a risk we take in gardening. Commercial orchards, too, have to account for the fact that they will lose harvests once every several years, and will need to replace trees that die over the winter.

In recent years, plant breeders (particularly in Ukraine and Russia) have been developing American/Asian hybrid persimmon varieties to grow in their cold climates. These tend to have some characteristics of both types. ‘Nikita’s Gift’, one of the most popular hybrids, is self-pollinating, stays more compact, and has larger and similar fruit to an astringent Asian persimmon. But, the tree is hardy all the way to zone 5 – much more than a typical kaki.

Whichever cultivar you grow, an older persimmon tree will always be hardier than a newly planted one. Young trees are much more susceptible to cold damage than large, well-established ones. Luckily there are some simple things you can do to protect your persimmon trees over the winter.

Protecting Persimmon Trees from the Cold

A mature, established persimmon tree has the best chance of making it through winter unscathed. But in their first few seasons, young persimmon trees can definitely benefit from some winter protection, even if they are hardy in your area.

Mulch

In late winter, mulch thickly (about 4 to 6 inches) around the base of the tree, leaving a few inches of space right around the trunk. The goal is to insulate the roots, but as the mulch breaks down it will also provide some nutrition.

The best winter mulches are natural materials that insulate but stay breathable. Wood chips, bark, pine needles, straw, and even evergreen branches (finally, a use for your dead Christmas tree!) are good choices. Leaves and compost can be used as well, but they may become compacted and keep the ground soggy – a recipe for root rot. When in doubt, combine materials to avoid compaction.

Believe it or not, snow actually makes great insulation. Consider piling up some snow around the base of the tree (leaving some space around the trunk). Whatever mulch you choose, be sure to rake it away in early spring. This allows the ground to warm up, which signals the tree to begin growing again.

Wrapping

Using a breathable tree wrap like this one will provide important protection for young fruit trees. It will insulate the thin bark from cold winter winds, but also protect it from the sun’s warmth during the day (especially if you use a light-colored wrap).

Why block the tree from heat? Aren’t we trying to guard it from the extreme cold? Yes – but, it’s the wide temperature fluctuations that are likely to damage young trees. Extreme cold at night followed by direct sun during the day will cause the bark to split, making the tree more susceptible to breakage, disease, and further cold damage.

As a bonus, tree wraps also protect against sunscald and rodents. Critters love to chew on the tender bark of young fruit trees – as you can see in the picture below of one of my own fruit trees.

Container Growing

There is a simple way to ensure that your persimmon survives the winter…plant it in a container! Asian persimmons, in particular, grow well in large pots, as long as the tree has enough space and is fertilized regularly.

A potted persimmon will stay more compact since its roots are restricted, which is good news for northern gardeners. The tree will be that much easier to wheel into a garage or shed for winter protection.

American persimmons probably won’t take kindly to container-growing, however. For one thing, they are much larger trees (50 to 80 feet). They also have a very long tap root, which just won’t have enough space even in a large pot. (Read more about persimmon tree size in How Big Does a Persimmon Tree Grow?)

Cultivar Choice

The main thing you can do to ensure winter survival of a persimmon tree (to the best of your ability) is to choose the right cultivar. Taking into account all of the considerations above – zone, winter precipitation, humidity, windchill, elevation, planting location, etc. – below are some of the hardiest persimmon varieties for northern climates.

The Most Cold-Tolerant Persimmon Varieties

Use the lists below to determine which persimmons will be best in your area. The zones and low temperatures are suggestions based on experience and extensive research, but of course, cold tolerance will vary depending on other factors.

American persimmons (D. virginiana)

The most cold-tolerant American persimmons (D. virginana) are ‘Meader’ and ‘Yates’, followed by ‘Early Golden’ and ‘Prok.’ Named cultivars such as these will have the best flavor and most consistent crops, though some wild persimmons may be hardier. Young trees will need cold protection the first few years.

| Variety | Zone | Low Temperature | Other Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Meader’ | 4 – 9 | -30°F/-34.4°C | bred in NH, may survive as low as -40°F (zone 3a), self-fruitful |

| ‘Yates’ | 4 -10 | -30°F/-34.4°C | native to Indiana, self-fruitful |

| ‘Early Golden’ | 4b – 9 | -25°F/-32°C | ripens early, partially self-fruitful |

| ‘Prok’ | 5 – 8 | -20°F/-29°C (-30°F/34.4°C) | usually listed as zone 5, but has been known to survive to -30°F (zone 4) or lower, self-fruitful |

Asian persimmons (D. kaki)

The most cold-hardy Asian persimmons (D. kaki) are ‘Great Wall’, ‘Tan-Kam’, and ‘Ichikikei Jiro’, followed by ‘Saijo’ and ‘Jiro’. The hardiest Asian persimmons will tolerate temperatures as low as -10°F(-23°C), but they may partially die back and not fruit the following season.

| Variety | Zone | Low Temperature | Other Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Tan-Kam’ | 6 – 9 | -10°F/-23°C | from Korea, self-fruitful |

| ‘Great Wall’ | 6 – 9 | -10°F/-23°C | discovered on the Great Wall of China, self-fruitful |

| ‘Ichikikei Jiro’ | 6 – 9 | -10°F/-23°C | compact (8-10ft tall), self-fruitful |

| ‘Saijo’ | 6b – 9 | -5°F/-20.6°C | may survive to -10°F (zone 6a), self-fruitful |

| ‘Jiro’ | 6b – 10 | -5°F/-20.6°C | may survive to -10°F (zone 6a), self-fruitful but will produce better with a pollinizer nearby |

| ‘Hana Fuyu’ | 7 – 10 | 0°F/-17.8°C | also called ‘Giant Fuyu’, self-fruitful, perhaps a little hardier than ‘Fuyu’ |

| ‘Fuyu’ | 7b – 10 | 5°F/-15°C | may survive to 0°F (zone 7a), but might not fruit the following season |

Hybrid Asian-American persimmons (D. virginiana x kaki)

The most cold-tolerant hybrid persimmons (D. virginiana x kaki) are ‘Geneva Long’ and ‘Rossyanka’, followed by ‘Mikkusu’ and ‘Nikita’s Gift’. American/Asian hybrids are more cold hardy than Asian persimmons, but with larger fruit and more compact growth than American varieties.

| Variety | Zone | Low Temperature | Other Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Geneva Long’ | 4 – 9 | -30°F/-34.4°C | may be hardy to -35 (zone 3b) or lower, self-fertile |

| ‘Rossyanka’ | 5 – 8 | -20°F/-29°C | may be hardy to -25°F (zone 4b) or lower, self-fertile |

| ‘Mikkusu’ | 5b – 9 | -15°F/-26°C | may be hardy to -20°F (zone 5a), self-fertile |

| ‘Nikita’s Gift’ | 5b – 9 | -15°F/-26°C | may be hardy to -20°F (zone 5a), self-fertile |